Painting The End of the World: Jessa Gilbert's Antarctic Travel Journal

by

"Do you think it's hot in here, or is it just me?"

I ask across the breakfast table as I strip my sweatshirt off over my head, feeling a wave of nausea set in. I catch eyes with Erin Bruhns over her omelet and recognize the concern on her face. "I think you should go change right now," she says while I hike my puffy pants up to my knees and feel the heat rising from my shoulders towards my ears. "Yeah… I should change, and then I'll feel fine," I think as I try to push myself up out of my chair that is fastened to the floorboards. I make my way as quickly as I can, swaying through the sea of tables and chairs, chained in their arrangements, down the stairs carpeted in a design of swirls and abstract shapes, and promptly through my bedroom door and directly to the toilet bowl. I made it, but just barely. The Drake Passage shook my stomach straight out of me, making me wonder if I'd actually leave the ship during the next ten days in Antarctica. I laid down on my duvet, damp and depleted, and closed my eyes. "How the hell did Shackleton do this voyage way back when?!"

I had packed my board bag and art supplies for this two-part expedition weeks prior to unpacking my stomach on that ship, the Ocean Diamond. I would be guiding with Ice Axe Expeditions on a splitboard expedition to Antarctica while simultaneously creating a body of artwork that would capture the experience of traveling to such a remote and historic part of the world. We would be leaving the port of Ushuaia for this journey, so I thought it best to explore that southern city, dubbed "The End of the World," prior to boarding the ship. I had never been to South America, so exploring its landscape, colorful cities, and the contrast between Argentina and Antarctica was enticing. Along for this journey were Matt Bruhns, Erin Bruhns, and Joel Loverin, all splitboarders from British Columbia and all thirsty for whatever this experience of adventure and art had to offer.

Part 1: Exploring "The End of the World"

The small city of Ushuaia was built into the prominent peaks at the Southern tip of Argentina. When we arrived, it was the tail end of their Spring, and the snow had mostly disappeared from the peaks around the city. Our splitboards stayed stowed, and our hiking boots came out. On the first day, we rented a car and drove towards the ocean-side city of San Sebastián to see how the coast looked and to try and spot Guanacos. Guanacos are llama-esque camelids that, after stopping the car a few times, we realized are sort of like deer here, as their herds are abundant. We stopped for empanadas and snacks, working through hand gestures and broken Spanish. No one seemed to mind our inability to communicate, as the World Cup was playing, and every Argentinian was fully engaged. Vamos Messi!

Beautiful trail networks surround the city of Ushuaia with waterfalls and wind-pressed foliage. The dark blue shores were littered with shells and neon green sea life, picked at by the various sea birds and wandering tourists. The landscape reminded me so much of our home in British Columbia, with its nearby islands, protection from the sea blasts, and snow-capped mountainous terrain. The main street had a European feel, with bakeries, shops, and restaurants proudly displaying their sea and land catches in the front window. Argentinians would likely say carne is king here, but the seafood was also rich and fresh. One of the most defining characteristics of this area would be the wind, a steady gale that kept coats buttoned to the chin and gloved hands in the pockets. Even the trees seemed to be permanently bracing themselves.

Part 2: Life Aboard the Ocean Diamond

After a week of wandering the landscape around Ushuaia, we boarded the 1973 Ocean Diamond ship along with the rest of the Ice Axe Expedition and Quark Expeditions guides and guests. We added a tail guide to our group named Max White, a skier-gone-splitboarder from New York City who had a sharp tongue and long stride. Myself, Matt, and Erin were East Coasters by origin, so he fit right into the fold of our group.

Our trip began with a two-day sail through the Drake Passage, a notorious body of water connecting the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean, extending into the Southern Ocean. To put that shorter… it was a far stretch of water that has the potential to get incredibly rough. (See the first paragraph for the effects of the "Drake Shake").

Part 3: Land (and Snow) Ho!

Eventually, I grew sea legs, just in time for our first objective: Deception Island. Swimming penguins and whales flanked our boat as we approached the C-shaped volcanic island best known for its old Norwegian Whaling station that ceased operation in 1967 due to a volcanic eruption. Steel containers reminiscent of a Richard Serra sculpture still stood upon shores, smoldered with steam and sulfur. There were a few buildings still standing, a crumbling foundation with a wood stove here and there, and a large dilapidated building that seemed to be waiting for its permission to lay down. Penguins and seals greeted us on land, uninterested in becoming compadres and more interested in heating their bellies on the warm sand. We curled around the buildings and made our way up a slope to a perch above the ship. The snow was soft and springlike and supported playful turns towards the ultramarine waters below.

We took the zodiac back to the ship and made plans for the following day's objective. Plan A was nixed due to weather, so Plan B became our focus - George's Point. This landing was a bit more complicated than the steaming beaches of Deception Island, as it required carving steps into the 10-foot wall of ice onto the glacier. The wind was light as we started up the glacier, but it began to turn quickly. We rode a couloir off the shoulder down towards the cracking glacier and floating ice just in time to get a radio call from our Expedition leader, Andrew Mclean, that all parties needed to head back to the ship. At first, it felt like a typical storm day - visibility became poor, snowfall increased, and the wind started to whip around us. We roped up, wrapped around the base of the couloir, and proceeded face-first into the strongest wind I've walked through on a split board. The gusts would blast with such intensity that we were occasionally knocked over or forced to batten down our stance and wait. One gust came so powerfully that it blew me sideways off the skin track and about 50 feet closer to the glacier's edge. We eventually made it back to the landing zone, where our zodiac driver reminded us to tighten our life jackets, hold onto the handles of the zodiac, and prepare to get lots of salt water in our faces as we returned to the ship.

All parties returned safely to the ship, and the captain swung the bow away from the gong show weather vortex and towards Lemaire Island, our next day's objective. I was part of the morning scouting party, meaning we'd take a zodiac early to the shore to sculpt a landing that would safely allow all guests entry into the landscape. Myself and Jorge Kozulj, a guide from Bariloche, were ushered to shore by a French man named Fabritz who rode the zodiac's steering column like a bull while sporting a sun-bleached pink puffy from decades prior with patches reading "Toby the Polar Pig." No gloves, scarf, or hat for this wild seaman. His kit made me feel soft with my thick gloves, goggles, and a balaclava pulled up to my eyeballs.

This landing was unique as it supported a major colony of gentoo penguins, a small tuxedo sporting bird with neon pick excrement and a voice more similar to belches from a donkey than songs from a chickadee. I don't know how long we stood on the shore, locking eyes with these birds, their chests proudly displayed and their arms stretched back while they waddled towards us as if to say, "clip me into the rope, I'm coming with." The less curious penguins remained sheltered next to a small Argentinian Army/Naval building, making it appear they had overrun the Argentinian military and made themselves at home.

Eventually, we started shuffling a skin track through a fresh dusting of snow towards the peak, which sat above a light blue wall of ice. The clouds began to break during our transition and gave us a full view of the ocean below, with floating icebergs and small ripples made from a pod of humpback whales. The scale of this place felt infinite, and the ice and snow-caked shores seemed to float upon the surface, obscuring the definition of where the land ended, and the temporal ice forms began. I sketched small studies from my field book as I tried to wrap my head around the hypnotic tones of this location, all the while conscious of Antarctica's potential to shift swiftly and unapologetically to an inhospitable landscape. However, the penguins don't seem to mind at all.

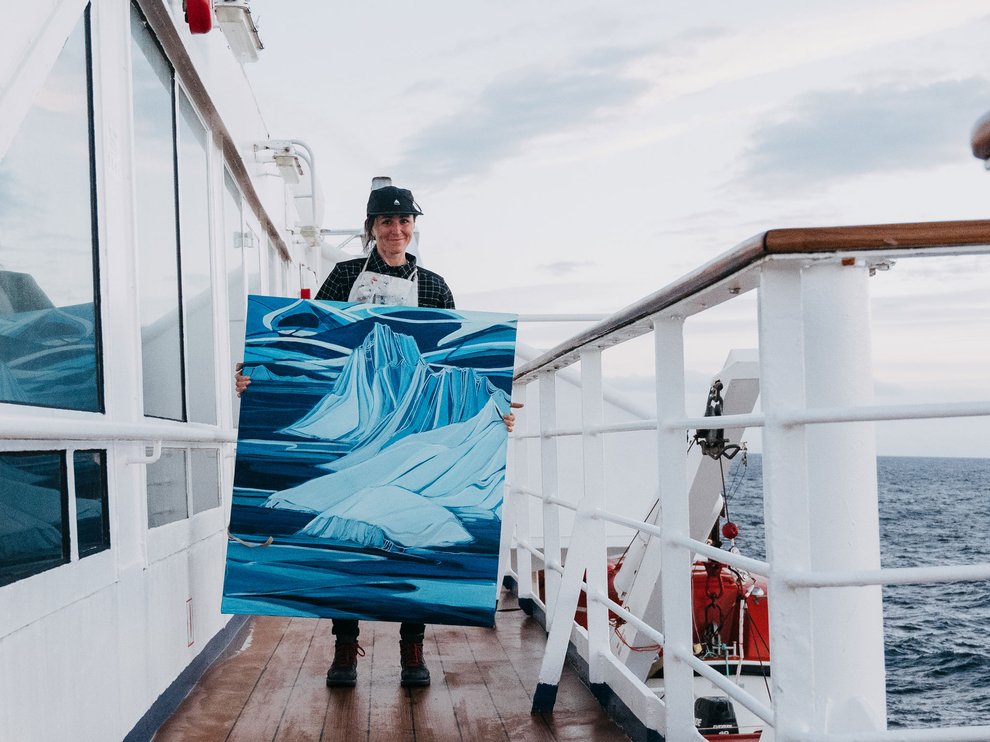

I began painting the canvas I brought later that day on the ship. I squirreled away a studio space on the top observation deck, with elevated views over the bow. My goal with my artwork has always been to try and capture the tones of adventure and to celebrate wilderness and its awe-inspiring qualities. As I worked towards the composition, I considered the connections between the creative process in painting with the creative process in moving through the mountains. Both require curiosity and are built one step at a time, whether moving a paint stroke through space or a skin track through glaciers. I've painted all my life, and love applying that creative process to the mountains with my split board. So often, we talk about "painting a line down a mountain" when looking for aesthetic places to place a track. The intention, to me, is the same, but the medium shifts from paint to powder. I chipped away at this painting throughout the rest of our expedition whenever I would find a moment, each day inspiring a tweak in the color and composition of the artwork.

It was fun to work on that painting between moments on shore and directly from the experience we were having. In many ways, I wish I had brought multiple canvases or had infinite time as the land, ice, color, and tones of the experience starkly shifted each day. Our marks felt temporary on the surface of the snow, and through the floating icebergs, so the permanence of paint assisted in cementing the experience for me. For five days, we'd land our zodiac on the shores and have our minds moved by the life and landscape abundant in Antarctica, and for five nights, I'd work my paintbrush along the canvas to try and hold onto the fleeting feelings of this adventure.

Our final day was calm, with a clear blue sky and a supportive slope for a skintrack that could weave between the ice bulges and open cracks of the glacier. I unclipped the group from my rope and rode my split board down through a hallway of glacier ice towards the glittering teal and navy ocean below. I could feel the heat from the sun on my face, the warm corn snow under my board, and a welling up of emotion in my gut. I looked down at the nose of my board as I pointed it towards the Ocean Diamond, feeling grateful that such a fun and playful passion could be harnessed for travel and creativity. I chose a spot to regroup below the slope while I let myself become lost in thought. I heard my crew come in behind me, laughter loud and high-fives a plenty. We finished our Antarctica splitboard experience with a party shred down to the waiting zodiac, some sporting tears of joy and awe… self-included.

Part 4: The Return to Ushuaia

Our travel back to the port of Ushuaia was an even rougher two-day sail through the Drake Passage. We splayed our seasick bodies around the ship, reminiscing about the past week's wild weather, penguin colonies, and fun descents. What a wild split board adventure this had been. Up the skin track or down the slope, splitboarding has offered me a new connection between art and adventure that can be applied to local mountains or faraway landscapes such as the slopes of Antarctica. What a tool for play, exploration, and creative pursuits; painting lines up and down snow-covered landscapes. Even Shackleton seemed to understand the importance of having an artistic eye on these expeditions, as he employed an Artist to join each trip he made to Antarctica. I may not be as tough or willing to weather as those previous explorers, but the new tools and fresh perspectives make me feel connected to those previous expeditions. I like to think they, too, would have enjoyed laying their own snowboard turns upon the landscape.